A prior post dealt with transferring into Waterloo Engineering from some other program or university. More frequently, the question is “can I switch to X Engineering if I start in Y Engineering?” (where X and Y are two of our own engineering programs). This is an “internal transfer” process, so no OUAC application is necessary and there is a bit more flexibility. But it is also potentially more confusing, so let’s look at some scenarios. Continue reading

minimum admission requirements

Transferring to Waterloo Enginering

Another common question during our admission cycle is whether someone can start a program (let’s assume engineering) at another university, then transfer into Waterloo for 2nd or 3rd year. These might be people who didn’t get an offer to Waterloo, or maybe want to try another place first but keep their options open. The short answer is that yes, it is technically feasible, but the likelihood of successful admission to 2nd year is pretty low. Here are some of the major reasons why: Continue reading

Boosting Grades at Summer School

While working through our application and admission data, we see quite a few applicants who have done a required course at summer school, especially among Ontario residents. (It doesn’t seem to be so common in other provinces. I wonder why?) We know that the theory/rumour is that you can get higher grades at summer school and thereby boost your admission average and chances of acceptance into the more competitive programs. We also hear concerns from other applicants and parents that this is an unfair advantage, because some are unable to attend summer school for various reasons. Currently we don’t penalize applicants taking summer school courses (unless it is to repeat a required course), but maybe we should? Since we like evidence-based decision-making, let’s use some data to see if summer school does give a significant advantage. Continue reading

How to Get an Early Offer

Lots of applicants are keen on getting an “early offer”, which for Waterloo Engineering is typically in the early March to early April timeframe (the final offer round is in early May). There is no particular benefit to getting an early offer, other than relief from the stress of uncertainty. Actually, there is a downside: a few people with early offers relax too much and lose out on scholarships (which are decided in May) or sometimes even lose their offer when their final grades come out. But most are OK, so how to get one of these early offers? Following is a list of things to do: Continue reading

Chance Yourself

On the College Confidential forums, there are whole sections where applicants ask others to “chance me” (a rather odd use of “chance” as a verb, but anyways). They post their stats and desired target colleges, and want others to tell them how likely they are to get an offer. It is primarily U.S. college focused, so I thought I would develop a system where you can “chance” yourself for Waterloo Engineering, as an extension of what I discussed in the post about cut-offs. Continue reading

Engineering School Selectivity

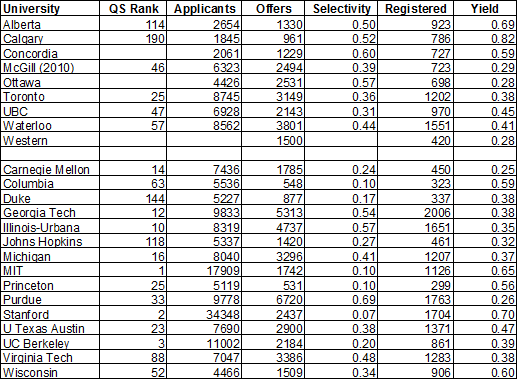

When comparing universities there is a statistic that some people like to use called “selectivity”. This is simply the ratio of (# of offers)/(# of applicants). So, a school that has a lot of applicants and only sends out a few offers is considered to be “highly selective”, because their ratio will be very low. Selective schools are sometimes viewed as more “prestigious” by administrators, parents and applicants.

This is not the whole picture however. There is another interesting statistic called “yield”, which is the ratio of (# registered)/(# offers). If this number is low, it means that a school sends out many offers that are not accepted by the applicants. There are various reasons why this might be high or low, but to illustrate let’s look at some real data for 2011. The following table was constructed using data from the American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE) college profile database, which you can access at this link: http://profiles.asee.org/ From this database, we can look up the number of applicants, offers, and registrants (i.e. those who accepted the offer and attended that school) for Canadian and select US engineering programs. Then we can calculate the selectivity and yield for each, as shown below. I also added the QS Engineering and Technology University Ranking, where available.

First, you might notice that a few Canadian schools are missing from the table. There was no information in the ASEE database, so I presume they didn’t participate in the survey, and Western was missing one piece of data. The McGill data was only available up to 2010, so I listed that instead. For the U.S. schools, I just randomly selected a few well-known ones from the top end of the QS rankings.

Comments:

Looking at selectivity, we see the hyper-selective U.S. schools such as MIT, Stanford, Columbia, where the ratio is 0.1 or less. There is nothing in Canada that is quite that low. It looks like UBC is the most “selective” in Canada, followed closely by Toronto, McGill and Waterloo. These selectivities are not much different from many of the well-known and highly ranked U.S. schools like Michigan.

Looking at yields, Calgary comes out on top at an amazing 82%, with Alberta not far behind. The only U.S. school coming close is Stanford. Why are these Canadian yields so high? I suspect is has to do with the amount of local choice. In Calgary, you either accept the offer to your local engineering school, or move away some distance, so the tendency is for higher yields. In southern Ontario where there are many choices within a reasonable driving distance, the yields are lower. Likewise in the U.S., the highly ranked UC Berkeley is quite selective, but has a relatively low yield because there are plenty of top engineering schools to choose from in California.

Admission offices in universities are usually quite aware of their yield values. They usually send out more offers than they actually have space for, knowing that only a certain fraction will likely be accepted. It is sort of like airlines over-booking their seats, knowing that a few passengers won’t show up or will re-schedule.

Consider also that there is a connection between selectivity and yield. If a school tends to have a high yield, they will send out fewer offers and that will drive down their selectivity ratio. And vice versa. So, although people tend to compare just selectivities, they can’t really be viewed in isolation. I’ve run across rumours that some universities try to drive up the number of applications they receive, so that their selectivity ratio will be driven down and they will appear to be more “selective”. Certainly the hyper-selective U.S. schools don’t need to encourage more applicants. Getting admission there is already more like a lottery than a selection process.

You might think that highly selective schools would be ranked higher, so I plotted the selectivity versus QS Rank. It looked like a random scatter graph, so there is no obvious correlation between selectivity and QS Rank (which is all reputation based).

Finally, looking under the column labelled “Registered”, we can compare the relative sizes of Engineering programs in a few schools. Waterloo appears to be the largest in Canada, but is still quite a bit smaller than some U.S. schools like Georgia Tech. Is a smaller school better than a larger one? I think that’s more of a personal preference, and there’s no clear correlation between QS ranking (reputation) and the size of the school. My view is that a larger school offers more opportunities to interact with different faculty and other students.

What’s the Cut-Off?

Around this time of year, “What’s the cut-off?” is probably the most common question we get about admission to our engineering programs. A very reasonable question, and one that helps potential applicants know their chances for admission. Unfortunately, it’s a question we can’t really answer. Not because we’re secretive or trying to be coy, it’s just a question without a direct answer for a number of reasons. Continue reading

University Rankings: Macleans Professional Schools

The Canadian magazine “Macleans” does university rankings, and recently they published their “2012 Professional Schools Rankings“. I think you have to pay to see it, or buy a hardcopy. I have a subscription, and can summarize some of the information here. Continue reading

Repeated Courses and Why We Care

Admission to our Engineering programs requires the completion of certain Grade 12 courses (or equivalents in various other school systems), specifically Functions, Calculus, English, Chemistry and Physics in Ontario. For many years we have discouraged the idea of re-taking any of these required courses to boost marks and get a competitive edge for admission. In recent years, this has taken the form of a penalty of around 5% points off the overall average of the required courses if one or more are repeated (the higher grade is used). The net effect is that unless the repeated course(s) add at least another 30 percentage points to the total, repeating a course is not worthwhile for competitive advantage in admissions. In many cases, repeating course(s) will knock the application out of the competition completely. Other universities seem to have a range of approaches, from accepting repeats without question to ignoring the improved grade completely. So, we’re somewhere in between. But why use this penalty approach? Continue reading

Engineering Admissions by Lottery?

The Tenured Radical blog on the Chronicle of Higher Education website has a post reflecting on the possible use of a lottery system for admission to competitive universities. Under this system, we would just identify everyone who meets our minimum admission requirements (maybe an 80% average for the required courses?), then run a random selection process that fills the seats. There are some tempting reasons to do this. Continue reading